Hopping the Coal Train

A critical fabulation exploring the mines of 19th century Pennsylvania

HISTORYESSAY

On May 2nd, 1893, Henry Kesspier was getting ready to head home from his shift at the coal mine. Henry was a signal boy. The station he worked at was deep within the mine, a long walk at the end of the day. His boots were too big, and his footsteps were heavy. After a full day of work, he was already worn out, bangs flattened against his forehead in a slurry of sweat and dust. A long walk was the last thing he wanted. Luckily, the day’s last train of minecarts was just beginning to leave, headed outside the mine. As they picked up steam, Henry hopped on, standing on the bumpers between two of the carts, feet jostling in his too-big boots as the wagons rolled over the rails.

Henry wasn’t supposed to ride the train like this, but he’d done it before. Enough times to know that the foreman wouldn’t do more than scold him for it and that the driver didn’t care enough to tell him to walk. More than anything, he knew that there was nothing to worry about. It was a simple ride. Nothing special. Nothing to get bent outta shape over. He just wanted to get home.

Sulfuric air blew by as the train rattled towards the mouth of the mine. The rattling shook the wagons which shook Henry’s too-big boots which shook Henry’s feet inside his too-big boots. One big jolt shook it all, and Henry lost his balance. He fell between the carts and cried out as they crushed him, loaded with rock and coal. It took only a couple seconds for the driver to notice what was going on and stop the train. But after those couple seconds, Henry only lived for another two hours before succumbing to his wounds. Henry Kesspier was 13 years old.

CONTENT WARNING:

This essay concerns the death of a minor and child labor.

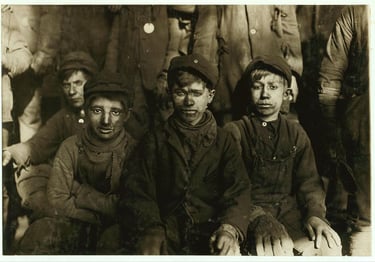

By Pennsylvania law, the minimum age required to work in a coal mine in 1893 was 13 years. That year, 249 boys under the age of 16 worked in the coal mines of Pennsylvania’s third bituminous district. Henry Kesspier was just one of them. School was no necessity, and money was hard to come by, so these boys worked to support their families. They sorted coal and ran signal lines and crawled through tight spaces. For their sacrificed childhood, many developed respiratory conditions like asthma or black lung, lost fingers or limbs in accidents, or were killed.

The official report of Henry’s death states that both his foreman and the station driver had frequently forbidden him from riding the trains [2]. But Henry was a 13-year-old boy. 13-year-old boys don’t tend to take orders very seriously, nor do they typically understand the potentially drastic consequences of their actions. They want to seem grown up and unafraid of danger, especially when in environments ruled by older, grizzled men, like that of a coal mine. They want to fit in. They want to feel just as manly as all of the other men around them. Perhaps that’s what young Henry was doing when he jumped onto those wagons– living up to the ideas of masculinity that surrounded him.

Or maybe Henry was just having fun. Being a bit of a shit, at least in the eyes of his bosses. It’s not some leap of logic to think that this 13-year-old boy got a thrill out of jumping onto a moving train and riding it to the pinprick of sunlight at the mouth of the mine. Getting bounced along the track. A rush of air on his coal-dusted face. The relief of ending a shift. Perhaps he was just excited for the freedom of the evening and the promise of something fun to do, away from his job in the mine. Maybe the mine car ride was nothing more than an expedited trip to that freedom. A quick journey out of the jaws of adult authority.

What young kid wouldn’t be excited about that?

In the official report of his death, there’s a telling lack of compassion for Henry Kesspier. The description is written by the safety inspector of the third bituminous district of Pennsylvania, one Thomas K. Adams. Adams does not waste a word over the loss of Henry Kesspier. The very first comment he has to make about Henry’s death is the assurance that Henry did not die on company time. “But rather,” Adams writes, “[Henry] was stealing a ride” [2]. Immediately, blame is expunged from the mine itself, and Henry is cast in a thieving light, stealing a ride on a cart like a hobo hopping trains. Adams never discusses the reality of Henry’s childhood, nor does he lament the death of this youth.

This report, for all of its dress as a safety report, is chiefly concerned with the cost of human life– particularly in its justification for the loss of it. Mr Adams is quick to concede that the rate of fatal incidents in the district had risen from two in 1892 to three in 1893. However, the inspector is also quick to note that, for each death, there was 1,074,710 tons of coal produced, which was, as Adams put it, “a very satisfactory showing” [2]. The numbers are there. Fatalities occur, but the mines are producing, so the inspector is satisfied. The loss of life is justified by the fruits of dangerous labor.

The morality of Henry Kesspier's child labor bore no weight on the pocket books of the mining company. He had been a cheap, exploitable form of labor, and his death brought nothing but the headache of bureaucratic red tape for his superiors. It was a failure of systems and profit-driven priorities that led to Henry's tragically early death in a Pennsylvania mine.

Fig 1. Hines, Lewis Wickes. “Group of Breaker boys. Smallest is Sam Belloma, Pine Street.” Library of Congress. 1911, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018676230/.

Fig 2. Hines, Lewis Wickes. “Breaker boys working in Ewen Breaker of Pennsylvania Coal Co. For some of their names see labels 1927 to 1930.” Library of Congress. 1911, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018676221/.

* References *

“Pennsylvania Mine Accidents 1869-1916: SURNAMES Ker-Kle.” USGenWeb Archives. http://files.usgwarchives.net/pa/1pa/xmisc/mineaccidents/ker-kle.txt.

“Reports of the Inspectors of Mines of the anthracite and bituminous coal regions of Pennsylvania, for the year 1893.” Internet Archive. Pennsylvania Inspectors of Mines, Edwin K. Meyers, 1894: Harrisburg. https://archive.org/details/reportsofinspect1893penn.

"Child Labor in Pennsylvania." Internet Archive. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1998. https://archive.org/details/ChildLaborInPennsylvania.

Get in touch!

Reach out directly :)

joelatroutman@gmail.com

Or use this form thing!