by: Joel Troutman

An Analysis of Traditional Chapbook Printing Techniques and Using Them to Make Memes

Making ye olde Memes

The Goal of This Project

Two things that I really like are artistic mediums that are traditionally seen as "cheap" and memes (bit of an overlap there, eh?). Something that's really fascinating to me about old school, cheap shit is the effort required to make things that are so commonly dismissed as low class, unimportant, or separate from art itself-- especially back in the day, when computers weren't around to make creation much easier.

This brings me to chapbooks. During my last semester at school, I took a class called "Literature, Media, and Science in the Age of Shakespeare" which acted as a survey of culture in England during the Renaissance. Cool class. Learned a lot. Didn't, though, learn a lot about these little things called chapbooks. We touched on them briefly during one lecture, and that was it. Being a cheap form of literature produced for the common folk, I was instantly interested and wanted to learn more. And what better way is there to learn about a thing than making the thing? So that's what I set out to do!

I'm going to research and analyze traditional chapbooks in order to make an eight-page-long chapbook-- complete with hand-carved images and actual, hand-set type-- about memes. Nowadays, this is just called making a zine, but I'm approaching it as a chapbook for ~historical~ purposes. You can argue that having memes as my subject matter fits with the socio-economic target audience of traditional chapbooks as well as their rapid culture turn-around, but honestly, I just thought it was a funny idea. Like, who the hell would put so much effort into making memes? It's basically an academic shitpost.

We'll get to the finished project by the end (or you can just skip to it now-- I can't control you), but first we have to ask some questions and do far too much research.

What's a chapbook?

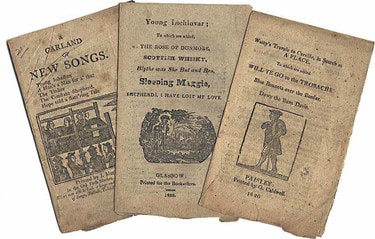

Traditional chapbooks are booklets made of one or two sheets of paper, folded and bound into books of 8, 12, 16, or 24 pages. They were cheap little things, intended to be read by common folk. Their topics range from fairy tales and poetry to politics and religious sermons. As long as there was an audience for it, there was a publisher making chapbooks about it.

With the rate of European literacy growing following the Renaissance, chapbooks were a pretty big deal. More people were reading than ever before, and for a few centuries, chapbooks were a vital part of both communication and storytelling. Their importance only died off as magazines and penny dreadfuls replaced them during the end of the 19th century. (Check out this source if you wanna learn more about chapbooks!)

* Research Stuff *

So, in order to make my olde memes, I need to do some research. I have two main goals for the research itself:

Identify chapbooks that told history or shared information

Analyze their styles/techniques in order to apply them to my own chapbook

Most of my research is coming from two main places:

National Library of Scotland

Digital collection of chapbooks printed in Scotland

Mainly from 19th century

Pretty well organized and documented

McGill University Library

Digital collection of chapbooks printed in the UK and America

Mainly from 19th century

Lots of info and history about chapbooks

There is one big problem with my research sources: finding old chapbooks. I wanted to find old, Renaissance era chapbooks in order to emulate their specific style. However, I just couldn't find any! Pretty much all of the digital chapbooks I could find were from the 19th century, which is, you know, old ... but not as old as I wanted. Unfortunately, 16th century chapbooks just don't seem to exist. It's simply an unavoidable part of reality. Chapbooks were cheap and disposable. It makes sense that there aren’t a ton of examples out there from the Renaissance, since many of those chapbooks likely didn’t survive-- either breaking down from age or getting tossed in the trash. Whatever the reason is, they're not really around anymore. Which sucks. But 19th century ones will just have to do.

History, I guess?

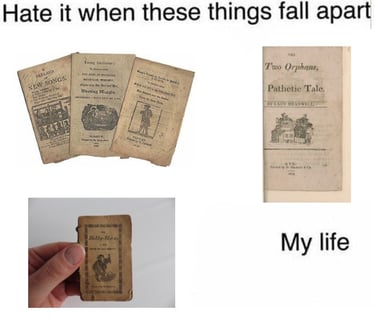

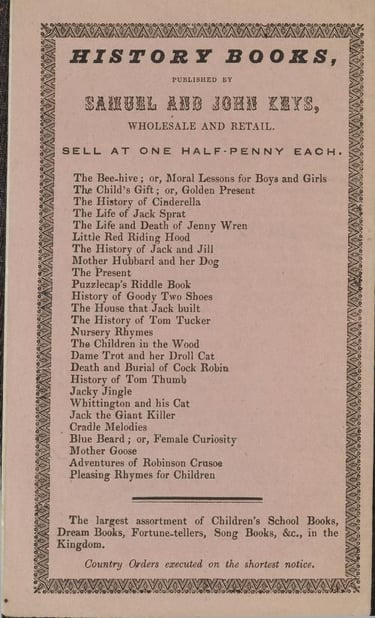

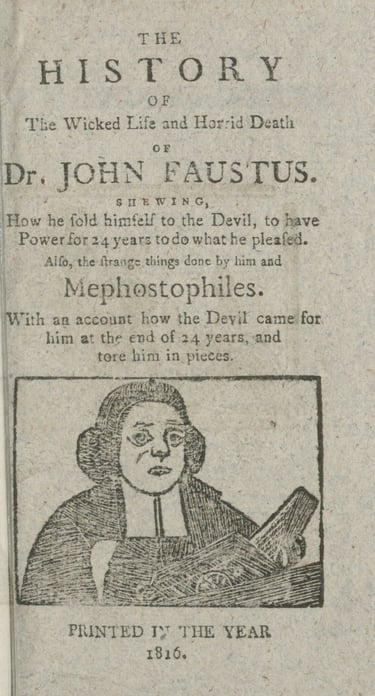

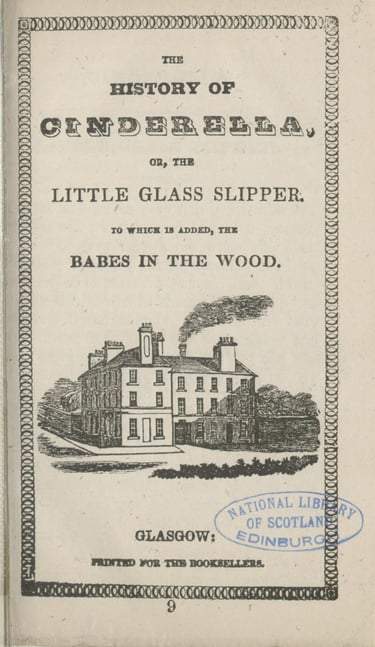

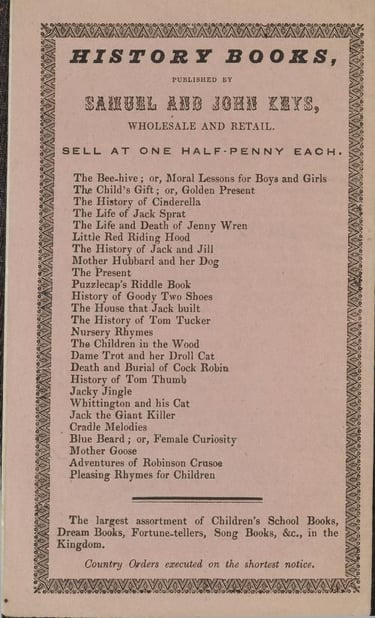

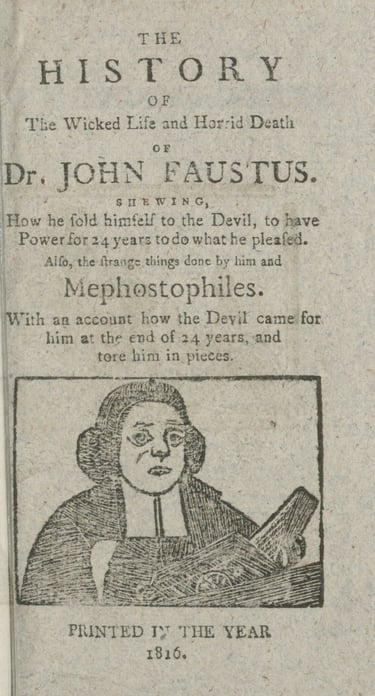

(These are some of the "histories" I found.)

So, I did some reading and found a bunch of narrative chapbooks that are sold as “history books” but are definitely not historical at all. I found some stories I was familiar with, like Robinson Crusoe, Dr. Faustus, and Cinderella, and all of them read pretty similarly to what I know them as, except their titles all start with "The History of ..." It's a small difference, but when I'm trying to identify and analyze historical chapbooks, these things stand out to me. And it made me wonder: did readers think Cinderella and Jack the Giant Slayer were actually historical figures?

I can't assume readers were gullible enough to confuse fairy tales with fact. Instead, I began wondering if this was something similar to Thomas More’s Utopia, a totally fictitious novel sold as a real-life travel journal describing an island that didn't actually exist. I assume these aren't the same thing since Utopia's pseudohistory was such a big deal at the time (and because More himself wasn't a particularly popular dude). I also have to assume that readers were smart enough not to take all of these legends and stories as fact. But I can't be certain of that. So ...

Well, no. At least, probably not.

The History of history

(the word, that is)

I dug into the meaning of history. I looked at this website which then pointed me at some old sources and gave me some insight about finding my own old sources. In the end, I got three pretty decent sources: one Middle English definition, one 19th century Latin definition, and a Victorian English definition. Let's see if we can learn anything from them!

histori (Middle English):

A tale, story, biography, legend

historia (Latin):

A narration of past events

History (English)

A written statement of what is known; an account of that which exists or has existed; a record; a description.

Alright, so we have these three definitions, and looking at them, we can see a story play out through time.

The Middle English definition comes from ~1393 and is made up of three words that are types of fiction and one word that's associated with non-fiction. It's pretty open-ended with no real sense of veracity attached to it.

The next definition is Latin, which is an old language, but the definition itself isn't super old. It comes from 1879, and compared to the Roman Empire, that's not that old. This definition is solidly focused on the past, though it doesn't assert any sort of truth to its "narration."

Our last definition is from 1886 and comes from a guy named Webster. This one is pretty much in-line with our modern understanding of history as a concept. It covers a lot of bases but is rooted in the knowledge of the past.

Putting these three definitions back-to-back-to-back, we can see a trend towards truth, though it's still not a totally certain one. Our stories are definitely playing off of the first two definitions more so than the last one, telling stories that may have happened in the past. But this isn't very conclusive. As insightful as these definitions are, the explanation behind the titling goes beyond the meaning of history itself (that means more research).

So I began wondering if this was just a quirk of the times, which then led me to Geoffrey of Monmouth's The History of the Kings of Britain. It's a 12th century work that was originally written as history but is now known to hold little-to-no actual historical value. What value it does have comes from its legends and tales, such as Jack the Giant Slayer and the stories of King Arthur and his pals. Where I find a potential connection is its use of "The History of ..." in its title. I wondered if that may have influenced the titles of these stories, but I couldn't find anything confirming nor denying it. Dead end.

I ended up finding some general info about publishing during this time and the rise of historical fiction. The article I looked at notes that, following the popularity of Robinson Crusoe, historical fiction took off. So I figured publishers may have been trying to capitalize upon this trend by calling everything "A History of ..." But, again, I could find no consequential evidence proving this one way or another. This titling phenomenon was something I wasn't going to figure out without dedicating a chunk of time researching the philosophies of fiction titles in the 19th century. As interesting as this rabbit hole was, I'm just chalking it up as a weird quirk of the times and am just going to ...

Yeah ... I just need to move on.

(This part is too long and not very important -- you can skip it if you want)

Actual Travel Narratives and Histories

(Some actual historical chapbooks and travel narratives I found)

With some more researching, I found actual travel narratives and informational chapbooks. There’s a fair bit of variation in the styles of writing between these works, ranging from dry ass, white bread history to personal and reflective travel journals.

Out of these chapbooks, the one I connected with the most was called "Awful Phenomena of Nature! Burning Mountains." This is an informational piece about volcanoes, studying Vesuvius and Mount Etna, amongst others. Its prose has an academic tone that’s actually kind of close to Galileo’s work in The Sidereal Messenger. It's smart and informative but also accessible with some poetic lines and creative metaphors. What we get in "Burning Mountains" reminds me of a scholarly conversation– similar, perhaps, to more modern histories that are intended for a wider audience. It's really nice! I liked it a lot.

There's a good deal of overlap with the strategies in each of these. They all have long titles and are collections of information, rather than ultra-focused dives into a subject. Even "Ancient and Modern History of the Russian Empire" pulls things apart by chunks to make its history easier to chew (though it is stale as all hell). The three besides "Russian History" are also much more opinionated. Their writers (who are largely anonymous themselves) inject "insight" and give a certain slant to whatever they're writing, for better or worse (usually worse).

How Does Any of This Apply to my Work?

Alright, with my far-too-deep research done, it's time to move onto actually making the thing. I went into it with a few strategies that I think I largely kept to and one I picked up along the way.

Hand-cut memes and physically print them (this was the whole point of the project in the first place)

I just thought the idea of seeing memes presented in a serious, scholarly way would be funny.

Present a collection/field guide

Whether it was poetry, news, or fiction, almost all of the chapbooks featured more than one piece of writing/covered a variety of subjects.

Memes as something to study

Part of the informational, scholarly thing meant that I needed to actually present some information and context for these memes.

Comedy

The whole point of this was to be funny. If it isn't then it's just a lame bit of shitty linocut memes and words.

Duke of Frogtown

In the process of actually constructing it, I ended up inventing the "Duke of Frogtown" as an actual character. He's a British nobleman/aristocrat who takes himself too seriously and looks down on things he doesn't understand. This was another layer of goofiness that I thought was fun and fit with the theme. Hopefully it isn't too much.

Actually Making the Thing

I wanted to make as much of this zine chapbook thing physically as I could, rather than digitally. In the end, it was about 50/50. But honestly, that's fine.

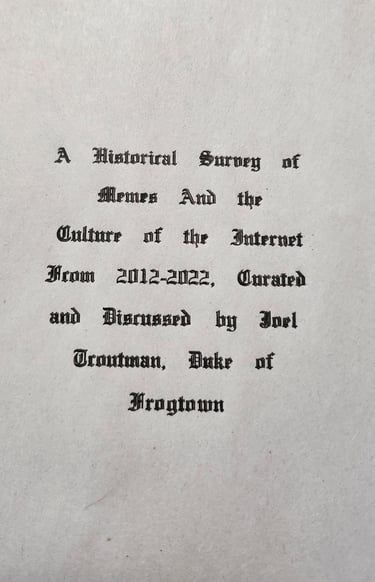

The title page was handset and printed at the University of Pittsburgh, which has a printing press that's open to students. Typesetting that was fun. I wanted to do the whole booklet that way, but I graduated before I could finish it. Whoops. (This whoopsie saved me a lotta time. Like a lot of time.)

(Typeset pictured here is mirrored for the sake of reading it.)

(My name is crossed out in the final zine to prop up the Duke's character.)

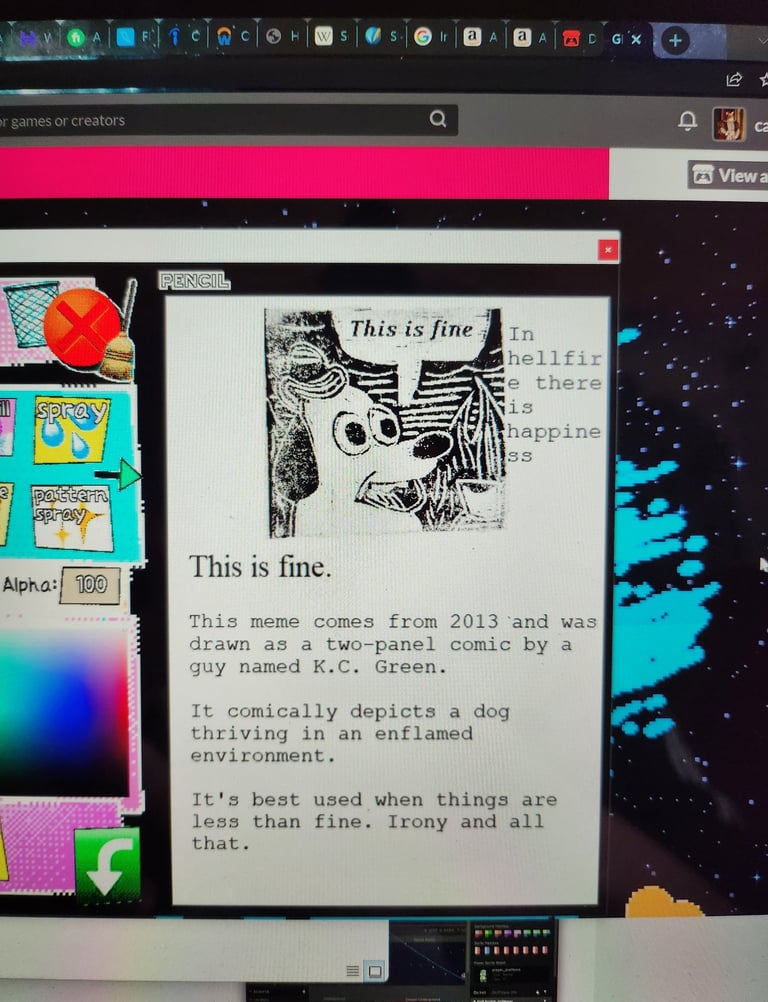

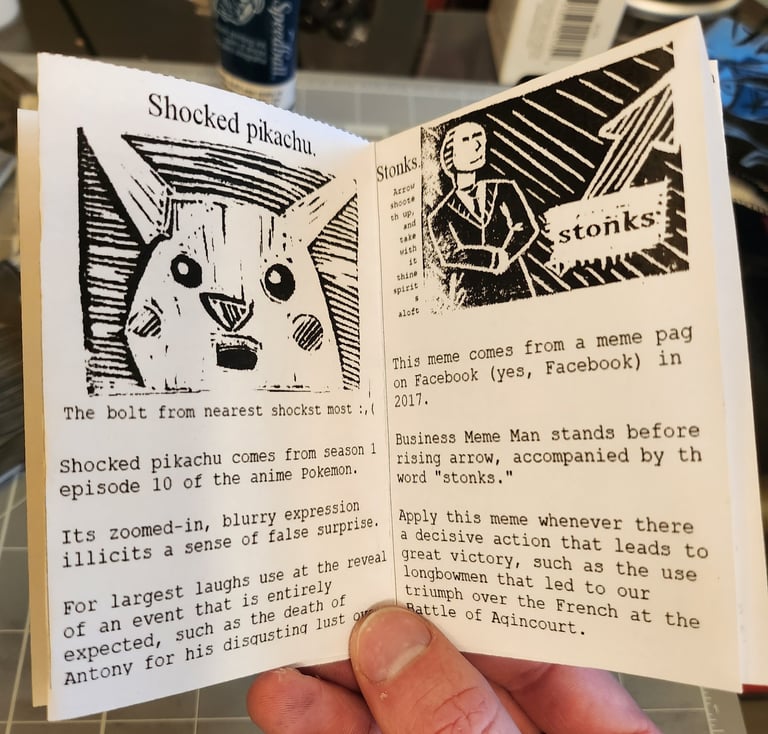

My "Historical Survey of Memes" had to showcase a variety of memes. I tried to be academic about it. The memes I chose span about a decade of time and cover a swath of styles and usecases. It starts simply with This is Fine and ends up getting weird and surreal by the time we get to Stonks, M&M Dr Phil, and, of course, the Raccoon memes. If I put on my art historian's beret, there's a lot of analysis that can go into the cultural and artistic study of memes, but I won't be getting into right now. Just know that I could (this is a threat).

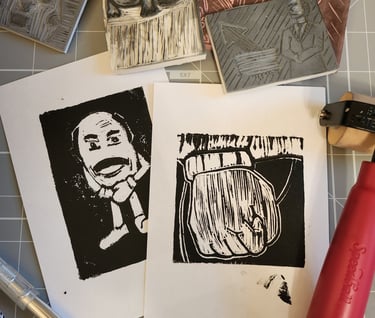

Memes selected, I then had to carve them. I had never done linocutting before and hadn't done any real art stuff since my 8th grade art class, so I really wasn't expecting anything from myself. That said, I'm pretty happy with how they turned out! They're shitty, but in a ~charming~ way. The process was also pretty fun and has sparked something artistic within me.

(Linocut memes and a couple messy prints.)

That concludes the extent of the physically-made stuff. I digitized the title page and a print of each of the linocuts (just scanned them with my phone and processed them with GIMP) and then put it all together with Electric Zine Maker. The layout and construction of the zine is where I came up with the idea for the Duke of Frogtown. I used him as a funnel for the goofy typesetting and as a mouth-piece for the melodramatic "poetry" that accompanies each meme. So if you thought any of that was lame, blame the Duke. It was him, not me.

(Electric Zine Maker is a silly little free program that's pretty easy to use. If you're interested in making something like this, check it out!)

Check out the Zine/Chapbook!

All of that research and labor went into making an eight-page zine/chapbook thing. In general, I'm really happy with how it turned out! It's really silly and goofy and dumb, but that was exactly what I was going for. Hopefully some people can find it and get a little chuckle at the charmingly-shitty memes and maybe laugh at The Duke of Frogtown's outdated commentary. All-in-all, this was a really fun project that I'm glad to see finished.

If, for some reason, you've read this entire article without checking this thing out, you can find it here! You can read it for free digitally on itch.io, or you can order a physical copy from Etsy for $6 (comes with a shitty meme print, too!!!).

* Works Cited *

“Account of a dreadful hurricane which happened in the island of Jamaica, in the month of October, 1780.” National Library of Scotland. Dunbar: George Miller, 1799, https://digital.nls.uk/104184219.

“Ancient and Modern History of the Russian Empire.” National Library of Scotland. Edinburgh: John Morren, 1813, https://digital.nls.uk/104184369.

“Awful Phenomena of Nature! – Burning Mountains.” National Library of Scotland. Scotland: John Miller, 1826, https://digital.nls.uk/104184294.

“Awful Phenomena of Nature! – Earthquakes.” National Library of Scotland. Scotland: John Miller, 1826, https://digital.nls.uk/104184293.

“Chapbooks and Literacy.” McGill University Library. https://digital.library.mcgill.ca/chapbooks/nodes.php?p=009.

“Chapbooks.” National Library of Scotland. https://www.nls.uk/collections/rare-books/collections/chapbooks/.

Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. “A new Latin Dictionary.” Internet Archive. New York/Oxford, 1879, https://archive.org/details/LewisAndShortANewLatinDictionary/page/n871/mode/2up.

Geoffrey of Monmouth. History of the Kings of Britain. Translated by Aaron Thompson, with revisions by J.A. Giles. In Parentheses Publishing, Cambridge, Ontario: 1999, https://www.yorku.ca/inpar/geoffrey_thompson.pdf.

“Great messenger of mortality, or, A dialogue betwixt death and a lady.” National Library of Scotland. Edinburgh: John Morren, ~1800, https://digital.nls.uk/104184405.

“Histori and historie.” Middle English Compendium. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/middle-english-dictionary/dictionary/MED20899/track?counter=1&search_id=21139450.

“History of Cinderella, or the little glass slipper.” National Library of Scotland. Glasgow: [between 1840 and 1850], https://digital.nls.uk/104185169.

Marlowe, Christopher. “History of the wicked life and horrid death of Dr. John Faustus.” National Library of Scotland. Falkirk: Thomas Johnston, 1816, https://digital.nls.uk/104184857.

Roden, Bex. “The History of Historical Fiction, in brief.” History Through Fiction. https://www.historythroughfiction.com/blog/history-of-historical-fiction.

“The voyages and travels of Sindbad the sailor / as related by himself.” McGill Library’s Chapbook Collection. Devonport : Samuel and John Keys, [between 1840 and 1845], https://digital.library.mcgill.ca/chapbooks/fullrecord.php?ID=7432.

“Tournament at Eglinton Castle.” National Library of Scotland. Glasgow: Orr & Sons, 1839, https://digital.nls.uk/104185877.

Webster, Noah. “Webster's complete dictionary of the English language.” Internet Archive. London: George Bell & Sons, 1886, https://archive.org/details/websterscomplete00webs/page/628/mode/2up. University of California Libraries.

“Woodcuts from 18th-century chapbooks.” The Public Domain Review, Oct 8, 2012, https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/woodcuts-from-18th-century-chapbooks.

Get in touch!

Contact me directly :)

joelatroutman@gmail.com

Or use this form thing!