The history of history

a journey of historical linguistics and the weight of writing important things

HISTORYWRITING ABOUT WRITING

The etymology of history is a stupidly annoying thing to search. The keywords get all fucked, and Google ends up giving you a mix of articles about etymology itself and historiography, which isn’t quite what I’m after. So I dug through some old dictionaries in order to figure it out while exploring the subject of history along the way!

The impetus for this search comes from a fun quirk I found while looking through some stories from the 16-19th centuries, which is that a lot of them are described as “histories.” If you’ve read my making-of post for my chapbook zine, you probably have a good idea of where this is going (you’re also a total BABE). Doctor Faustus, Jack the Giant Slayer, and Hamlet, are three of the self-described “histories” I found. Folks may have been more superstitious in the olden days, but I didn’t think they truly believed these fairy tales were actual, historical events. Just because the word history has such a truthful connotation nowadays doesn’t mean it meant the same thing a few hundred years ago. So based on that hunch, I decided to look into the meaning of the word history itself.

I made this meme for one of my final projects at Pitt. I'm very proud of it.

Since I’m not a big library guy and don’t own any ancient dictionaries, I went on archive.org and searched around. There, I found some digitally dusty dictionaries to compare some similar-but-not-quite-the-same definitions. Here they are!

histori (Middle English):

A tale, story, biography, legend (2)

historia (Latin):

A narration of past events (1)

History (English):

A written statement of what is known; an account of that which exists or has existed; a record; a description. (3)

So what we see here is a breakdown of the definition’s evolution. The word “history” comes from the Latin “historia.” As time goes on, French takes from Latin and English from French until we get the Middle English term “histori.” Around the end of the 19th century, Webster gives us a modern definition of “history,” which is pretty much in-line with how we think of history from a 21st-century perspective.

This evolution shows how the idea of “history” changed from a catch-all term for any story of the past to a record of “what is known.” The Latin “narration” and Middle English “tale” are both steeped in storytelling rather than the factually-interested records and accounts that Webster’s definition promises (or at least as factual as any human record can be). This refocusing can easily be ascribed to the Enlightenment’s intellectual interest in reason and rational thought, pioneered in historiography by the likes of Voltaire and Gibbon.

Getting Definitive

We can use this knowledge of the term’s evolution to then explain the titling phenomena I discovered earlier. At least, in part. If “history” had a less-factual definition in the olden days, then it makes sense that its use would coincide with historical fiction or even straight up legends, like Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain from ~1136 which is now known not as a historical document but as the inspiration for King Arthur’s legendary knights of the round table.

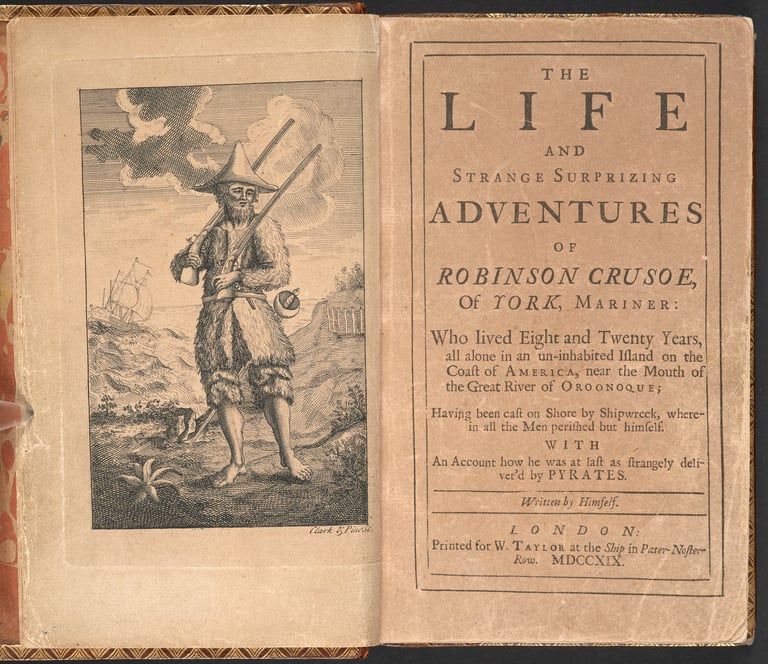

This period’s interest in realistic/historical fiction also has a role to play. In 1719, Robinson Crusoe was released. Daniel Defoe (unrelated to Willem Dafoe) posed the story from the perspective of Crusoe and gave the novel a sense of realism that readers bought into. This was such a shake-up for the literary world that it created the realistic fiction genre, laid the groundwork for the literary realism movement, and even helped invent the modern novel. Robinson Crusoe was a pretty big fucking deal!

In the years following Crusoe, there was a surge in historical fiction imitating its style. This trend continued for quite some time, influencing the titles and subject matter of novels up through the 19th century, when the term “history” was still loosely used for damn-near everything. You can find this in works like Henry Fielding’s The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling and Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, considered two of the first historical fictions ever published (4).

Looking at literature

The original title of Robinson Crusoe was:

The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who lived Eight and Twenty Years, all alone in an un-inhabited Island on the Coast of America, near the Mouth of the Great River of Oroonoque; Having been cast on Shore by Shipwreck, wherein all the Men perished but himself. With An Account how he was at last as strangely deliver'd by Pyrates. Written by Himself.

Shortening it was not a bad idea.

In the history of the written word, our modern concept of “history” is still a fairly recent thing. Which is weird to think about. At least, I think it’s weird! Such pillars of academic knowledge feel unshakably ancient to me. So sometimes I forget how recently scholars began taking things like female anatomy and ethics seriously. It was only about 150 years ago when Darwin hesitated to release his theory of evolution because he was worried about religious backlash. That world, operating in the shadow of the Church, isn’t that far-gone (and arguably isn’t gone at all!).

As a writer, the weight of academic/unbiased writing is something I find incredibly suffocating. I struggle writing pieces focused on the veracity of its subject matter, communicating "the truth" to readers who trust me to know what I'm talking about (which I'm sure is a great thing to read at the end of a post like this lol). There's a quote from Richard Slotkin's article "Fiction for the purposes of history" that actually assuages some of these feelings for me. Slotkins says, "History is what it is, but it is also what we make of it. What we call 'history' is not a thing, an object of study, but a story we choose to tell about things" (5). This perspective of a writer's interpretation of the world and their telling of it helps me understand my own place as someone who wants to learn and spread knowledge. Anyone that communicates ideas like these must act as a mouthpiece for their own perception of things. History is the conveying of facts and their intertwinings, but it's also still storytelling. I find comfort in the idea that everyone who does what I'm doing goes through the same respectful balancing act with their own writing. It's a nice idea.

How do I make sense of this?

Those Latin and Middle English definitions of "history" may be simplistic and outdated, but there is real truth to them, especially when taking Slotkin's ideas into account. Delineating between historical accounts and straight-up fiction is a good thing, don't get me wrong, but I get where those old understandings of the concept were coming from. There's sense to them. And at the end of the day, everything we know to be true comes from the understandings of scholars long-past. While they may have had some zany ideas about what was academically acceptable, learning about the operations of old academia can help ground our modern perspectives on history as well as my own grappling with the weight of writing important things.

* References *

https://archive.org/details/LewisAndShortANewLatinDictionary/page/n871/mode/2up

https://archive.org/details/websterscomplete00webs/page/628/mode/2up

https://www.bl.uk/restoration-18th-century-literature/articles/the-rise-of-the-novel

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232825192_Fiction_for_the_Purposes_of_History

Stick around and read some more stuff!

Get in touch!

Contact me directly :)

joelatroutman@gmail.com

Or use this form thing!